Forget Pi Day. We should be celebrating Tau Day

As a physics reporter and lover of mathematics, I won’t be celebrating Pi Day this year. That’s because pi is wrong.

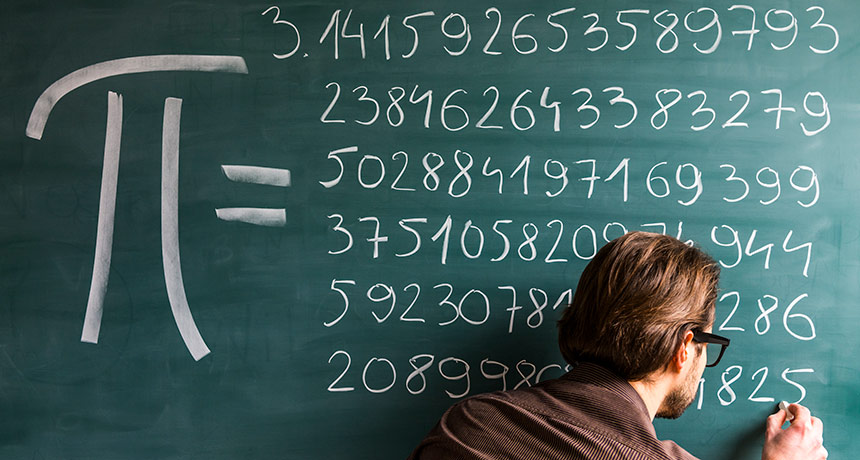

I don’t mean that the value is incorrect. Pi, known by the symbol π, is the number you get when you divide a circle’s circumference by its diameter: 3.14159… and so on without end. But, as some mathematicians have argued, the mathematical constant was poorly chosen, and students worldwide continue to suffer as a result.

A longtime fixture of high school math classes, pi has inspired books, art (SN Online: 5/4/06) and enthusiasts who memorize it to tens of thousands of decimal places (SN: 4/7/12, p. 12). But some contend that replacing pi with a different mathematical constant could make trigonometry and other math subjects easier to learn. These critics — including myself — advocate for an arguably more elegant number equal to 2π: 6.28318…. Sometimes known as tau, or the symbol τ, the quantity is equal to a circle’s circumference divided by its radius, not its diameter.

This idea is not new. In 2001, mathematician Bob Palais of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City published an article in the Mathematical Intelligencer titled “ π is wrong!” The topic gained more attention in 2010 with The Tau Manifesto, posted online by author and educator Michael Hartl. But the debate tends to reignite every year on March 14, which is celebrated as Pi Day for its digits: 3/14.

The simplest way to see the failure of pi is to consider angles, which in mathematics are typically measured in radians. Pi is the number of radians in half a circle, not a whole circle. That makes things confusing: For example, the angle at the tip of a slice of pizza — an eighth of a pie — isn’t π/8, but π/4. In contrast, using tau, the pizza-slice angle is simply τ/8. Put another way, tau is the number of radians in a full circle.

That factor of two is a big deal. Trigonometry — the study of the angles and lines found in shapes such as triangles — can be a confusing whirlwind for students, full of blindly plugging numbers into calculators. That’s especially true when it comes to sine and cosine, two important functions in trigonometry. Many trigonometry problems involve calculating the sine or cosine of an angle. When graphed, the two functions look like a series of wiggles, shaped a bit like an “S” on its side, that repeat the same values every 2π. That means pi covers only half of an S. Tau, on the other hand, covers the full wiggle, a more intuitive measure.

Pi has become so embedded in mathematics that it could be hard to excise. A more practical approach may be to introduce tau as a teaching tool alongside pi, rather than a replacement. Education is where tau’s impact is most likely to be felt: Professional scientists and mathematicians can comfortably handle the factors of two that crop up with pi in equations.

You might argue that multiplying by two isn’t that hard, even for students. But it isn’t the arithmetic that concerns me. Trigonometry is notorious for creating a divide between the math-fluent and math-phobic. But helping more people understand and enjoy mathematics isn’t some pie-in-the-sky fantasy. Everyone is capable of doing math. We just need to work smarter, and speak more clearly, to help those who struggle.

So here’s to June 28 — Tau Day.